The Phantom Drummer - Burrow Mump

Burrow Mump - Burrowbridge - Somerset

History-

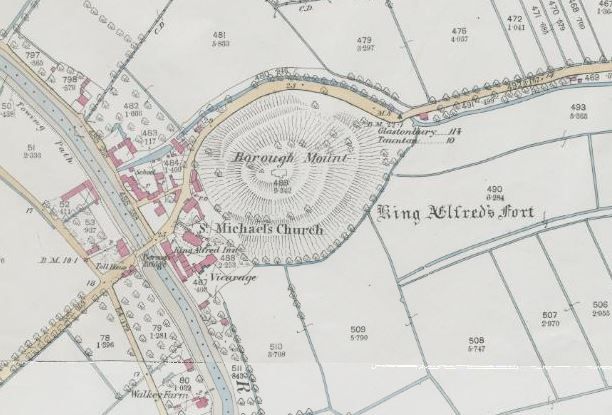

Burrow Mump is a hill and historic site overlooking Southlake Moor in the village of Burrowbridge in Somerset.

It is a scheduled monument, with a never completed church on top of the hill a Grade II listed building.

The monument includes a motte castle formed from the top of a natural conical hill, with a terraced track spiralling up to it, an unfinished church on the summit, and field and settlement features on the lower slopes.

The hill stands at the junction of two rivers crossing the flat Somerset Levels.

Although there is some evidence of Roman visitation, the first fortification of the site was the construction of a Norman motte.

It has been called King Alfred's Fort, however there is no proof of use by Alfred the Great apart from its ownership by the nearby Athelney Abbey which he established and was linked to Burrow Mump by a causeway.

It may have served as a natural outwork to the defended royal island of Athelney at the end of the 9th century.

The monument includes a motte castle formed from the top of a natural conical hill, with a terraced track spiralling up to it, an unfinished church on the summit, and field and settlement features on the lower slopes.

The hill stands at the junction of two rivers crossing the flat Somerset Levels.

The top 5m of the hill have been scarped to form a motte.

An approach track curves up around the south of the hill from the direction of the village below.

It stops short of the berm on the east, and the ascent would probably have been completed by steps.

Around the lower part of the hill on the north west, north and east are shallow lynchets, scarps and ditches, up to 0.4m high/deep forming a group of narrow or small enclosures along the edge of the road.

These represent agricultural and settlement plots, and lie between the village and surviving roadside settlement on the far side of the hill.

Such plots often resulted from squatter occupation in medieval times.

Burrow Mump is today crowned by a roofless unfinished church of the late 18th century.

A shallow hollow way leads up to the west end from the village.

The site has been thought to be associated with King Alfred's fortifications at nearby Athelney and Lyng, but though it seems likely that its strategic position would have been utilised, no evidence has been recovered to substantiate this.

The earliest reference to the hill is in AD 937 when, under the name of 'Toteyate', it was given to Athelney Abbey as part of the manor of Lyng.

Its association with Lyng survived until the 19th century in the parish boundary, which crossed the river at this one point to include it.

There is no further mention of the hill until more than four centuries after the Norman Conquest.

The castle does not appear in the Domesday Book of 1086, and either it had already passed out of use by this time, or was not constructed until later, perhaps during the years of The Anarchy in the early 12th century.

In a 1480 reference the hill is called 'Myghell-borough', and in 1544, 'Saynt Michellborowe' was part of the lands granted to one John Clayton by the king following the dissolution of the abbey.

The dedication to St Michael indicates a church or chapel, and in 1548 this is directly referred to as 'The Free Chapel of St Michael'.

The chapel was extant in 1633, but in 1645 was the scene of a short stand by 120-150 Royalist troops in the Civil War, who surrendered after three days.

The next reference is in 1663 when two shillings and four and a half pence from Corton Denham and one shilling from Langton were detailed for its repair and rebuilding.

This was apparently begun c.1724 but never finished, and by 1793 a new church was subscribed for, with contributors including William Pitt the Younger and Admiral Hood.

The building again was never completed, and remains roofless to this day, overlooking the later church of St Michael at the foot of the hill. Partial excavation on the top of the hill in 1939 revealed foundations of the medieval church, with a crypt in which was a burial with a lead bullet beside it, possibly from the Civil War skirmish.

A wall foundation on a different line associated with early medieval pottery was interpreted as part of the Norman castle.

There were also square medieval pits, post holes, a sunken passageway and finds of bones, pottery, coins, nails and lead bullets.

One of the square pits was sunk deeper than could be excavated and is perhaps a well.

The hill was given to the National Trust in 1946 as a memorial to those who died in the First and Second World Wars.

The ruined church is one of the churches dedicated to St. Michael that falls on a ley line proposed by John Michell.

Other connected St. Michaels on the ley line include churches built at Othery and Glastonbury Tor.

Hauntings -

Not a lot of reported activity here for such a fantastic historic landmark, just the eerie sounds of a phantom drummer which are heard..

Has anyone ever investigated here? or may live locally and know of any other stories at all?

© Somerset Paranormal

Sources - Historic England, Paranormal Somerset - Selena Wright

Photos - Newspaper - Somerset History & Mystery

Photo - imordaf on Pixabay & Sunset - credit unknown

#hauntedsomerset #somersetparanormal #ghostsofsomerset #burrowmump #supernaturalsomerset

Share